During my recent recuperation from a shoulder injury, one of the few things that I was able to do besides feel sorry for myself was to sit in a recliner with my iPad, and tap one-fingered with my uninjured right hand. I had the time to dig deeply into some previously overlooked family genealogy subjects. I was able to tap into resources I hadn’t looked at closely before, in particular, nineteenth century newspapers and city directories. One story that emerged from this research involves my great grandfather, John Alan Garde (1843-1900), and his younger brother, my great-grand uncle, William Henry Garde (1850-1907).

Michael Gard 1(1813-1872) and Catherine Coleman (1822-1892), the parents of John Alan and William Henry, emigrated from Ireland to Nova Scotia, and eventually settled in Cheshire, Connecticut in about 1844. John Alan Garde had been born in Nova Scotia; his younger brother William Henry Garde was born in Cheshire a few years later. Like so many Irish immigrant families, they came to the US with nothing. Michael Gard, the father of John Alan and William Henry, worked as a miner in Cheshire until the end of his days.

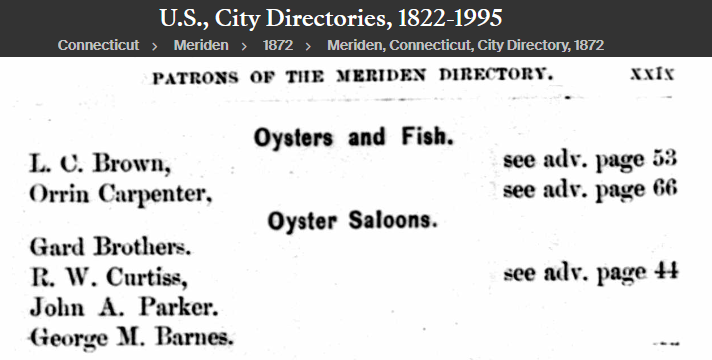

Having grown up together in Cheshire, brothers John Alan and William Henry moved to Meriden, Connecticut. Some time before 1872, they opened an oyster saloon together, under the name “Gard Brothers.” In the mid-nineteenth century, oysters were a cheap food, particularly in the coastal areas of Connecticut. Oyster saloons, a precursor to today’s fashionable oyster bars, were extremely popular; you can read more about them on Wikipedia. What Wikipedia does not tell you was that oyster saloons were sometimes associated with prostitution.2 Put a pin in that.

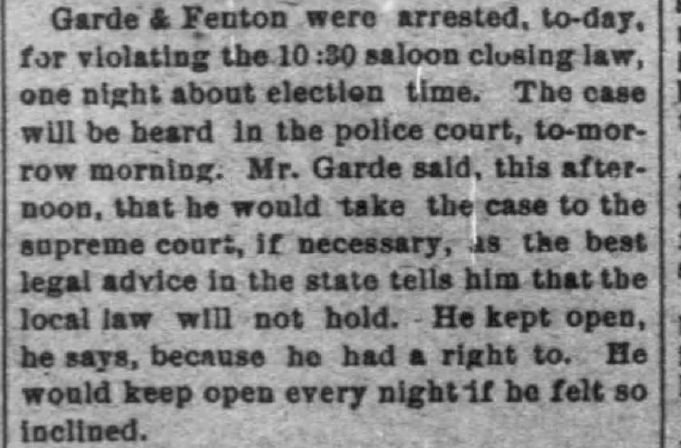

The partnership between the brothers didn’t last long. John Alan left the saloon business and did factory work for the remainder of his life. William Henry continued in the saloon business with other partners. In 1876 he was prosecuted for (and acquitted of) violating liquor laws, and in 1884 W.H. and his partner Albert Fenton were arrested for violating the saloon closing laws. Newspapers reported that Mr. Garde had announced his intention to challenge the law but it was shortly discovered that the partners had let their liquor license lapse. They were fined, and that appears to have been the end of the Sunday closing crusade.

1884 · P3

Despite these brushes with the law, W.H. became a very successful and well-known member of the business community in Meriden and the surrounding areas. His status in the community, including his involvement in politics, made him a frequent subject of items in the local newspapers. References to the doings of W.H. and his family in Meriden and Waterbury newspapers were common, including one item reporting on W.H.’s son’s hamster, on display in the window of the saloon. Newspaper items regularly remarked upon the health of William Henry, who suffered from a deteriorating condition that limited his activities and led to a series of out-of-town trips for treatment at various spas and medical institutions.

Despite his chronic health challenges, W. H. expanded into the hotel business. But eventually his health got the better of him and he passed on his business empire to his son Walter Sherman Garde. It was Walter Sherman who built a chain of Garde hotels and was responsible for building a theater that is now preserved as an historic site as the Garde Arts Center in New London, Connecticut. You can check it out here: https://gardearts.org/

The death of W. H. in 1907 at the age of 56 was widely reported. Many of the obituary items prominently mentioned that the debilitating condition from which W.H. had suffered for decades was “locomotor ataxia”; one newspaper included the cause of death in the obituary headline.

For decades prior to the death of W.H., doctors and scientists disagreed on the cause of locomotor ataxia, with some insisting that it was caused by an early infection from syphilis, but they had no scientific proof of their theory. Just before W.H. died in 1907, science resolved the issue when Dr. Wasserman developed a reliable test for syphilis. You may recall that for many years, getting a marriage license required an “blood test” – that was the Wasserman test for syphilis. Over the next several years after the test was developed, the hypothesis that locomotor ataxia was caused by syphilis was proved when virtually 100 percent of patients diagnosed with locomotor ataxia tested positive for syphilis.

By the time the link between locomotor ataxia and syphilis became widely known by the general public, W.H. Garde was dead and buried. But the question of his cause of death came up a few years later when his son Walter Sherman Garde was profiled in the prestigious Connecticut Encyclopedia of Biography, published in 1917. Walter Sherman had surpassed his father’s business achievements and was even more socially prominent than his father; his wife was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and when Walter Sherman died, the mayor of Hartford and the governor of Connecticut attended the funeral. There is another story entirely here about how the Irish became “white,” but I digress.

Walter Sherman Garde’s entry in the Connecticut Encyclopedia of Biography3 includes a lengthy account of the career of his father W.H. Garde, but the proprietorship of the oyster saloon was generalized into a statement that he had been involved in the “restaurant business.” The entry mentions W.H.’s health challenges, but locomotor ataxia was not in the chat. The entry reads: “William H. Garde was injured in the Wallingford tornado in 1878, and from that time until his death, which occurred January 28, 1907, he was a constant sufferer from the effects of his experiences at that time.” This is the first mention I have seen anywhere of W.H. being injured in the Wallingford tornado, out of quite a few news items that mentioned his degenerative condition and specifically identified it as locomotor ataxia. The Wallingford Tornado explanation sounds like fake news to me. (Side trip: the Wallingford Tornado)

I think it’s pretty clear that by the time the biography was being prepared in 1917, it had become well known that the diagnosis of locomotor ataxia meant that the person so diagnosed had suffered from syphilis. Syphilis was considered by some to be not only a physical illness, but a moral illness as well, particularly because it was understood that syphilis was a sexually transmitted disease often contracted by commerce with sex workers. It would not have done to mention such an unpleasant topic in and Encyclopedia of Biography published in Connecticut in 1917. Or even today, some may think. Of course, another possibility is that W.H. Garde’s publicly announced diagnosis was not correct in the first place, and that the symptoms referred to in news reports during his lifetime were caused by some other progressive condition.

It appears that John Alan Garde was suffering from medical issues in later life as well. An item in The Journal of Meriden, Connecticut, reported on May 20, 1892: “John Garde in Bad Shape – John Garde of Waterbury, formerly of Meriden, is in a strait jacket in the New Haven hospital suffering from delerium tremens.” Delerium tremens is a severe and life-threatening condition brought upon by withdrawal from severe alcohol addiction. But could John Alan’s health issues also have been caused by the end stages of syphilis infection?

John Alan Garde predeceased his brother W.H. Garde in 1900. Shortly before John Alan died at the age of 56, he was committed to the Connecticut State Hospital for the Insane in Middletown; he was buried in his home town of Cheshire. Although the court papers related to John Alan’s commitment are a matter of public record, they do not include a detailed diagnosis of the cause of his commitment. Was it chronic alcoholism? Or is it possible that John Alan Garde suffered from the long-term effects of syphilis? It is tempting to conclude that the medical issues suffered by the Garde brothers in later life have common roots, perhaps in the possibly morally loose environment of the oyster saloon in the 1870s.

It is not a stretch to suggest end-stage syphilis as a cause of death for men who came of age in the middle of the nineteenth century. Syphilis was regarded as endemic in the United States in the nineteenth century. During the Civil War, the prevalence of the infection was such that physicians examining draftees and enlistees were instructed to look for, and reject, those showing symptoms of the infection. The data gained from these examinations was compiled into a map issued in 1875 that showed the incidence of the infection in the Union states.

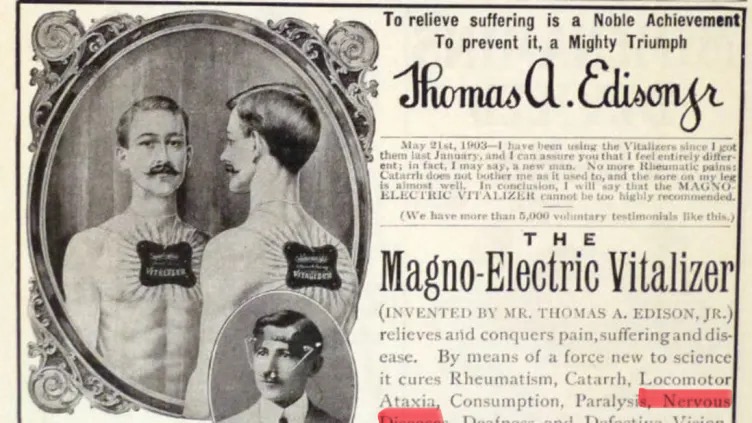

Evidence of the prevalence of locomotor ataxia in the nineteenth century can be found in the frequent mention of the condition in advertisements for patent medicines and spurious medical devices.

The “Magno-Electric Vitalizer” device was promoted by Thomas A. Edison, Jr., (son of the renowned inventor) before the company distributing it was shut down for fraud in 1904.

The most effective treatment for syphilis, the penicillin antibiotic, did not begin to become available until 1943. Sadly, way too late for the Garde brothers, if indeed their respective medical problems shared that common cause.

- The spelling of the family last name is inconsistent even between individuals. Father Michael Gard usually stuck by “Gard,” but as time went on, most family members eventually adopted the “Garde” spelling consistently. ↩︎

- One reference for this association is a blog post by Peter Jensen Brown, “Oyster Saloons and Brothels – a History of “Red-Light District,” (citing sources). https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2017/12/oyster-saloons-and-brothels-history-of.html#google_vignette ↩︎

- Encyclopedia of Connecticut Biography – Genealogical – Memorial – Representative Citizens (The American Historical Society), Vol. IV, p. 171 (Garde, Walter S. – Public Official). Available at ↩︎